El Chaltèn is still asleep when I take down my tent from the campsite where I’m staying, boil water for porridge and off I go, backpack on my shoulders, towards the entrance to the Park. On the first kilometers of the Vuelta al Huemul, a four-day circular tour in the Parque Nacional Los Glaciares, in Argentine Patagonia, the altitude slowly increases. The view of Fitz Roy and Cerro Torre is like in a postcard, on a very clear day without a cloud, a stroke of luck in these places so often afflicted by bad weather.

4Outdoor is also on Whatsapp. Just click here to subscribe to the channel and stay up to date.

The backpack weighs on the shoulders, because the trek must be done in complete autonomy, as far as sleeping (in a tent) and cooking are concerned. Water is instead offered in abundance by the many tongues of the Campo de Hielo Sur, which melt in the summer period.

In the woods, just before entering the Rio Tunel valley, I meet a German girl who will be my travel companion for the entire trek. We will divide the itinerary over three days instead of four, to add a few kilometers to the legs and a little more salt to an already demanding route: for this reason when we arrive at the first camp, at lunchtime, we move on after a short stop on the shores of Laguna Toro.

As we climb towards the glacier, the signs of its passage, and its retreat, are more than evident: we climb over sheepback rocks full of glacial streaks, until we reach the melting torrent. Here we are forced to take out our harness and longes, to cross the afternoon’s swollen river with a cableway with a steel cable over a narrow gorge a couple of meters, where the water roars a few meters from us, splashing our feet.

Among the ice

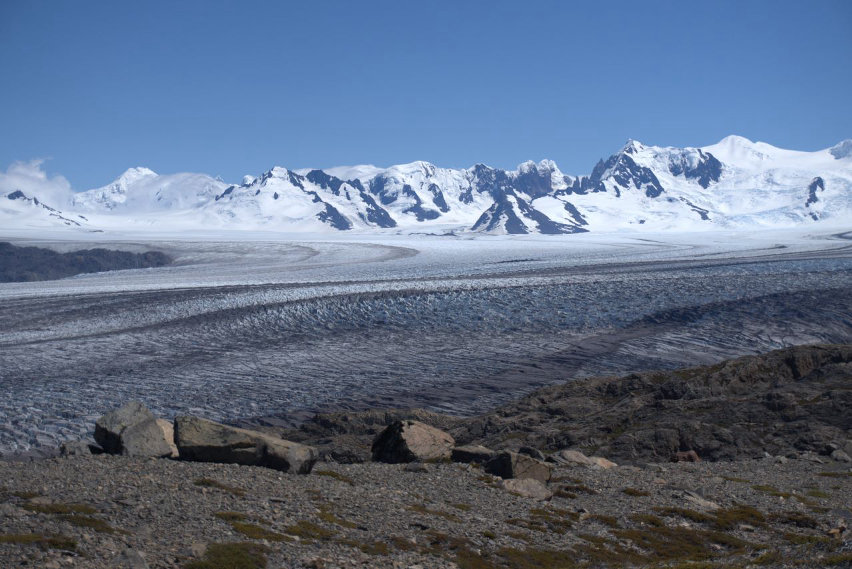

Once this test is over, the route begins to demonstrate its fame in terms of landscapes: from every side peaks emerge with white-laced crests, and with their glaciers that descend towards us, solid in the upper part and increasingly dirty with debris and crevassed in the lower part. These are precisely the views that I imagined when thinking of Patagonia, reading about this place so mythical and far away, where it seems impossible to have actually ended up.

Beyond the glacier, to be crossed by dodging the crevasses or hopping on the scree of the moraine, losing the path a handful of times, should be the first camping site of the trek. In fact, we pass a hill and see exactly what I was hoping for: the small pitches surrounded by stone walls – only on the side from which the famous Patagonian wind comes, with a view of the glacier and a small stream that will provide us with water for cooking. We are the first to arrive, but in the next few hours another five or six tents will be set up, while we are busy with the operations that immediately precede the night. Making water, boiling some dehydrated soup, huddling in our down jackets to watch the evening approach on the glacier.

Campo de Hielo Sur

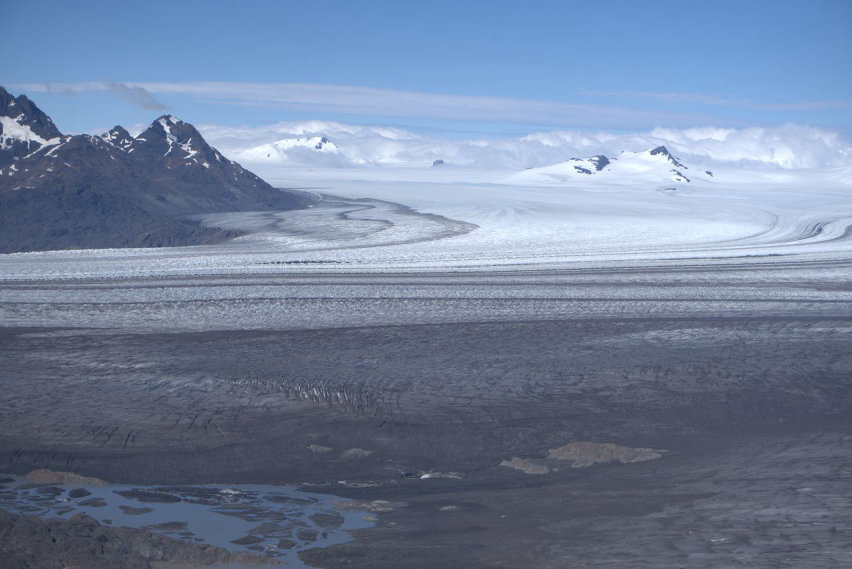

The night wind rumbles on the walls of the tent, shaking it and I begin to doubt the skill with which I have tied the guy ropes to the rocks. But they remain surprisingly attached to the ground, and the second day of the Vuelta al Huemul begins with a leg-breaking climb towards the Paso del Viento, whose name says it all. When I reach the top I am breathless, I don’t know if it is because of the climb or because of what I am seeing: the Campo de Hielo Sur in all its grandeur, a sea of ice that fills the valleys, from which only the peaks emerge, also snow-capped.

The white is streaked with gray and black, rocks of all sizes that the millions of cubic meters of ice move like a conveyor belt as they move downward. The whipping wind counts down the seconds I can enjoy the view, but the next twenty kilometers will all be along the glacier, and I will have the opportunity to observe it from multiple angles. The trail runs just to the side of the lateral moraines, hiding behind them at the lowest points but then immediately climbs up to open the view onto a new little piece of ice. Here is the only bivouac of the Vuelta al Huemul, the Refugio Paso del Viento, a tiny house that I imagine will be quite useful on the frequent days of bad weather.

Our legs are already pretty tired but we continue this ride on the edge of the Campo de Hielo, until we reach the point where the glacier (or at least this end of it) dies in a lake of grayish water. Every few minutes an iceberg breaks off and joins the others floating, hits the other shore and as the days, the months go by, it melts. The condors fly above our heads, very close, so big that they block out the sun for a moment and cast their shadow on the path. One last climb up to the Huemul pass and it’s time to say goodbye to the Campo de Hielo: we turn around one last time to look at it, who knows how many more years the third largest glacier on earth will be here, dragging down the debris that falls from the peaks and storing the world’s fresh water.

The lake and the Patagonian steppe

On the other side of the pass is Lago Viedma, a gigantic expanse of blue water. We descend headlong into the middle of the forest, until we reach one of the first little beaches, exhausted after twelve hours of walking. On the stony playa there is a little space to set up tents, and we share a soup and a packet of chocolate cookies while we listen to the icebergs roll over and break apart in the water of the lake in front of us. In the distance we can see the wall of the front of the glacier: a jagged wall, which falls in pieces and scatters them in the water, adrift for kilometers.

The icebergs are less frequent as we move away from the front, as we skirt Lake Viedma the next day. The temperature rises, a degree higher for every kilometer, and we are now far from the white and blue magic of the Campo de Hielo. We can already see the desert, the yellow steppe of Argentine Patagonia populated by guanacos and rheas, with the dry grass of this side of the Andes. It is time to get out the tools of the trade and attach myself to the cable to cross the river again, a few kilometers lower than the outward journey. Then I detach myself from the cable car, turn around and imagine myself still up high, inside that closed valley, wedged between the glaciers and the peaks, trying to guess the end of one of the gigantic Patagonian frozen hearts.

Elena Casolaro’s hitchhiking journey in South America continues. To follow it, you can subscribe to Strade, a newsletter that talks about kilometers, places and people, but above all stories. Iscriviti a questo link.