Photo: Martina Folco Zambelli/HLMPHOTO

To get back to producing frames in Italy, without losing competitiveness to Asia, you have to revolutionize the production cycle. There is no alternative… That’s what 3T has done and, in what way, we went to find out.

On this journey, our Virgil (although it would be better to say Beatrice, since we entered a kind of Paradise) was Enrique Romero Pineda, 3T’s production manager. An aerospace engineer with a background in carbon fiber processing, he is the one who organized the new factory in Presezzo (BG, Italy), in which the top-of-the-line models are made, with the goal of bringing the entire production, now relocated to the East, back to Italy within a couple of years.

Why did you decide to return to production in Italy?

“The reasons are varied and go beyond pride in Made in Italy. We also sleep the desire to be more competitive and to have more control over the quality of the product. In fact, each loom is traceable at all stages of production, which allows us to collect data that helps us understand and improve the process itself and also intervene in quality control, all with virtually zero reaction time.”

How did the reorganization of work take place?

“The first step was to analyze each phase of frame processing, to understand if and how it could be rethought from an Italian perspective, to adapt it to our goals and the size of a small company like 3T. Then, once we understood how to proceed, we had to modify or build from scratch some machinery that was essential for the new production method. We started to internalize the high-end models and we expect, within a short time, to bring all the production in house.”

How do the two manufacturing processes differ?

“The biggest difference is the percentage of the labor component. To make a chassis in Asia (Taiwan, China and now Myanmar and Cambodia), one has to manually put together a puzzle of 400 pieces of carbon fiber sheets and resort to special molds, requiring the work of multiple workers. All this translates into an average frame construction time of between 26 and 30 hours. Here, we have to go down to 8 hours to be really competitive. We are now at about 12 hours, and that is a good result.

To achieve this, we worked on three aspects: the first two are raw material and automation. From the so-called prepreg (carbon fiber already amalgamated with resin, a highly processed and therefore expensive raw material) we moved to yarn, the actual carbon fiber. It is a choice that, already upstream, gives us an advantage in terms of cost, minimum quantities and specific options depending on the bike model. To give an example, it’s as if to make a shirt you start with the thread instead of the fabric…. The same thing applies to resin, which we choose based on the chemical characteristics as it relates to its use.

The use of dry fiber, freeing itself from prepreg, is related to the choice of processing the raw material in a different way i.e., with the technology of “filament winding,” i.e. winding the fiber on mandrels. This is a widely known process, but we have developed it so that we can create geometries that have complex and stable shapes. Each tube is built with different amounts and textures of fiber, depending on its function, the stiffness you want to achieve, and, therefore, the type of frame. And the machinery with which this is done was designed and built by us, because there was a need to wind the yarn with maximum freedom of choice, in terms of angles and weaves.

At this stage of processing, we have also already achieved the goal of automation, as one person is able to follow up to four machines. Automation will also soon affect another stage of processing, as we will see later.”

What, however, is the third aspect on which the transition is based?

“It’s about energy efficiency. An aspect less related to processing time, but one that heavily affects costs: just think that, unlike dry fiber, pre-imoregnate has to be stored in the freezer at a temperature of -18°, to prevent the resin from hardening. This is a situation that involves high power consumption, and we will see more of this in the other stages of the production process. Also not to be underestimated is the impact of this on the quality of work. Think about having environments with constant temperature, with no fluctuations due to processing, or even the physical effort required by operations such as maneuvering large and heavy presses, compared to ours, which can be handled with minimal effort by one person.”

How do you get to the finished product?

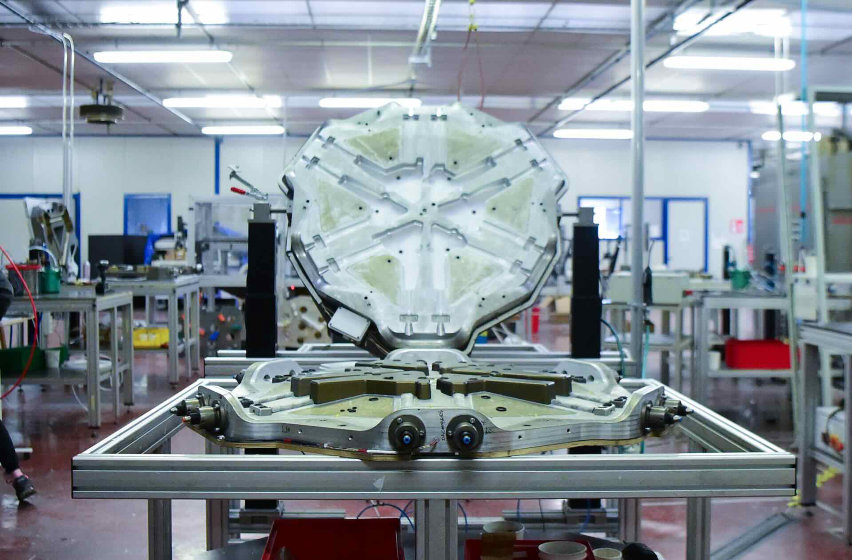

“The production process continues in the pre-forming room, where we create the parts that will go into the mold. Ninety percent of the bike frames we produce here are made using the filament winding method, while the remaining 10 percent are made using traditional sheet overlay technology. It is as if we work in this one by combining the skills of a tailor and a hairdresser. This is the most important step in the whole process, ending with the manual operation of cutting and “combing,” at the joints, and pre-assembly, before moving on to molding.

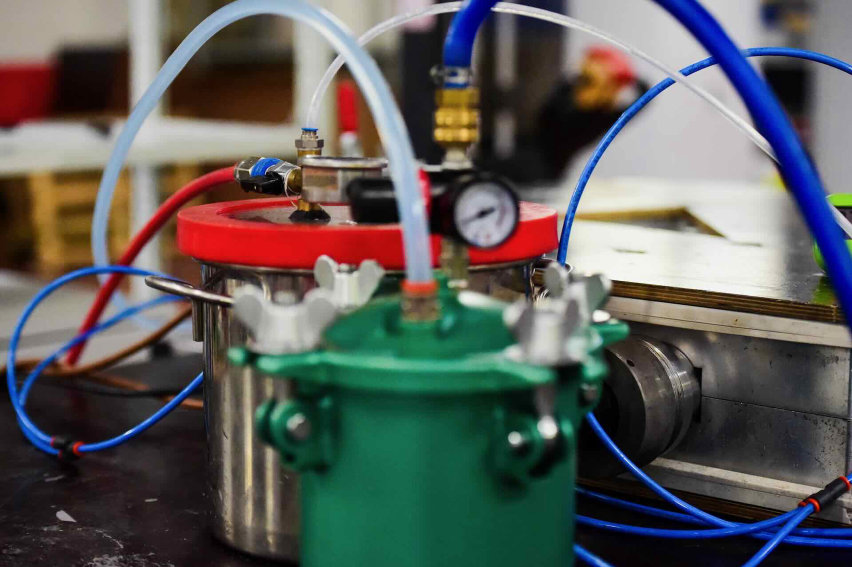

We operate according to the RTM (Resin Transfer Molding, or vacuum infusion molding of resins) process in which the carbon fiber structure is impregnated by resin, drawn through vacuum into the mold. Two of the three aspects on which we have based our production philosophy are also present at this stage. Raw material: compared to prepreg, the use of dry fiber allows for a molding process that requires lower pressures and temperatures. In addition, by being able to choose the resin based on its chemical reaction and curing characteristics, we can further affect the residence time of the semi-finished product in the mold. To give a practical example, if a prepreg frame requires processing at least 120° at 3 hours, we only need 80° and one and a half hours. Here is energy efficiency… Energy efficiency that also manifests itself at the time of gluing the carriage: instead of using a 2000-watt infrared lamp or an oven in which to put the whole frame, we built mini heated molds, acting only on the relevant section and consuming 175 watts.

The raw frames, cleaned and drilled, then move on to the last stage of the production process, finishing. If in pre-molding we had hairdresser and tailor, here we are almost at the dentist (smiles…, ed.). This is still manual precision work, but soon the sanding will be done by a robot that we are just finishing testing. And it is also thanks to the automation of this stage that we will go from 7/8 looms per day to 10/12, without changing the number of staff employed in production.

I end with one final note. An additional advantage of dry fiber, compared to prepreg, is that “pre-preg” frames often have micro pores, a peculiarity that is only cosmetic and has no structural repercussions, but which obliges further grouting, before sanding and, almost obligatorily, painting.

It is difficult for a far east frame to be offered as “naked” as our Project X, which with a comparison I really like, I consider the transposition on the product of our transparency as a company.”